|

International Journal of Academic

Research in Education and Review

Vol. 1(1), pp. 12–19,

September,

2013

ISSN: 2360-7866

DOI: 10.14662/IJARER2013.002

Full

Length Research

A Tapestry of Special Educational

Needs (SEN) in Mainstream Schools of London Boroughs

Shamaas Gul Khattak

Doctoral Student, Middlesex University

London. E-mail:

miss_khattak@live.co.uk

Accepted 16 September, 2013

This study focuses the issues and arguments about SEN and its

provision in mainstream schools. The objective of the study is to

evaluate the effectiveness and management of SEN to explore the

impediments in its affective way. The study based on qualitative

research paradigms for which in-depth semi-structured interviews

were selected tool for data collection. The sample includes the

headteacher, deputy head, SEN Co-ordinator (SENCO) and teaching and

teaching assistants (TAs) who were randomly selected from one of the

middle schools in London Borough. The methodology is content and

themes analysis to express the views and experiences of the sample

about SEN children, their attitudes, models of disabilities,

definitions and types of SEN and the support providing in their

school. Furthermore, critical discussion of the findings and the

methodological issues germane to the research findings elaborated

analysis of teacher’s perceptions towards mainstreaming SEN

students. The study concludes that lack of funds/resources,

inadequate SEN component in initial teacher-training curriculum and

untrained supporting staff make SEN provision ineffective in the

mainstream.

Key words: SEN, inclusion and exclusion, management, learning

difficulties.

INTRODUCTION

A great deal has been written about SEN because since the last

decade it has emerged as a key educational issue. This study

explores various aspects of the SEN provision and related issues to

co-related research findings with one or other aspect of the

existing research studies. This study is also a combination of mixed

findings of contemporary research studies. The selection of this

topic was due my personal interest and curiosity about SEN and its

provision in mainstream. Because SEN are of immense importance –

often the most critical factor contributing to the quality of

children lives in childhood. It is essential, therefore, to ensure

that the characteristics of SEN provision enable individuals to

optimise their abilities and to overcome, minimise or circumvent

their learning difficulties. The purpose of the study is to

investigate the process of inclusion and the supporting attitude of

schools within the existing frameworks of SEN. Many influences have

shaped the nature of provision for SEN. They include philosophical

and political standpoints, location, history and tradition, parental

views and the very different and changing needs of children. They

have resulted in an ever widening range of provision across schools.

What matters is that the provision made is suited to the

individual’s age, stage of development, and educational, social and

emotional needs. The starting point in making decisions about

educational placement is consideration of mainstream provision in

the individual’s own area. Most pupils with SEN in England attend

their local schools. Where the quality of the individual’s

educational and social experience is in doubt in such a setting, or

where it is not feasible to provide the exceptional levels of

support required, then other, more specialised forms of education

will be necessary. However, the overriding concern must be to ensure

that the SEN provision takes account of all-round needs and that the

individual is not socially isolated. This study is worth by

exploring the variation, elaboration and adaptation needed from

professionals to ensure continued effective provision to meet the

very wide and increasingly complex SEN now found in schools.

Furthermore the study highlights key features of SEN practice in

mainstream and provides a stimulus for further consolidation,

development and research.

Aims and Objectives of the Study

• To evaluate the meanings and understandings of SEN in mainstream.

• To ascertain types of SEN and how the students cope with their

peers.

• To triangulate the role of teachers, TAs and SENCO in an inclusive

environment.

• To map-out common impediments in effective inclusion.

Research Questions

The federal government has defined thirteen categories of

disabilities these included:

autism, deaf-blindness, deafness, hearing impairment, mental

retardation multiple disabilities, orthopedic impairment, other

health impairment, serious emotional disturbance, special learning

disability, speech or language impairment, traumatic brain injury,

and visual impairment (DfEE, 2001:13).

Keeping in mind the above list of disabilities, the main research

question and framework of this study was structured to investigate

whether the existing provision of SEN is effective, according to the

requirements of SEN students? Furthermore how to promote a

successful inclusion in mainstream?

LITERATURE REVIEW

This literature search conceptualises; definitions, features of

policies and practices and their implementation in the mainstream

schools. SEN were defined as physical or mentally disabilities under

the Education Act 1944, children with SEN were categorised by their

disabilities defined in medical terms. Many children were considered

‘uneducable’ and were labeled in categories; ‘maladjusted or

‘educationally sub-normal’ and given SEN in pirate schools.

A child is disabled if he is blind, deaf or dumb or suffers from a

mental disorder of any kind or is substantially and permanently

handicapped by illness, injury or congenital deformity (Legislation,

2005-6:7).

Furthermore, the Department for Education and Employment (DfEE,

1994:11) defined; A person has disability, if he has a physical or

mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term adverse

effect on his ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.

At time, only the physical or sensory challenged children were

considered SEN and the other learning disabled children were kept in

mainstream without noticing their special needs. However the limited

and specific meanings of the SEN become more comprehensive and broad

with the passage of time. The Code of Practice (DfES, 2001)

describes; children who have a disability which prevents or hinders

them from making use of educational facilities. However children who

speak English as a second language, their language problem is not

considered to be learning difficulty. The SEN students include all

learning difficulties groups, not just physically and mentally

disabled children, whether those children are facilitated with SEN

in special school or in the mainstream. SEN has been variously

defined, described or explained by different people at different

times. Their explanations are based on their individual, personal

and professional experiences and their cultural backgrounds. These

definitions of SEN are useless unless the provision can be

implemented which is only possible if an effective implementation of

SEN polices are developed in schools.

SEN Policies and Practices

The SEN policies can be traced back to the Education Act 1944 when

efforts were started for SEN provision in state schools. The SEN

concept in the mainstream was not introduced because the government

did not realise its need and importance. Although the Handicapped

and Pupils and School Health Service Regulations 1945, the Underwood

Report of 1955, the Plowden Report 1968 and 1970 and Handicapped

Children’s Act carried out their struggle for the effective

provision of SEN in the state special schools with special children

of physical/sensory or mental disability.

The Warnock Report 1978 and the Education Acts 1981 changed the

typical concept of SEN students and introduced the idea of SEN,

‘statements’ and ‘integrative’ which later became known as the

‘inclusive’ approach, based on common educational goals for all

children (Farrel, 2011). The introduction of SEN Children Assessment

Statements (CAS) encouraged the government to revise their SEN

policies in the mainstream but did not give additional funding for

the new processes involved in statements of SEN children or SEN

teachers training in special schools (Legislation, 2005-6). The CAS

and improper SEN teachers training programme block its effective

implementation in mainstream because parents complained the

ineffective long, time-wasting lengthy assessment procedure delay

the education of SEN students. However, the increased number of SEN

students increases the LEAs workload so their assessment tests

criteria change every year (Ofsted, 2007). Additionally initial

teacher training (ITT) failed to develop teachers’ skills and

confidence to help SEN children to reach their full potential in

mainstream (Golder et al. 2009).

The government inherited the existing SEN framework and sought to

improve it through the SEN and Disability Act (SENDA) 2001 and 2002,

and the 2004 SEN Strategy Removing Barriers to Achievement which

claimed to set-out the government’s vision for the education of SEN

children. The government substantially increased investment in SEN

but these policies worked well in their own frame of time and

targets, with major insufficiency of practical involvement of

mainstream SEN qualified teachers (Ainscow, 2013). Warnock et al.,

(2010) argue, teachers are ‘policy makers in practice’ and the

importance of teachers’ professional judgments in SEN implementing

is a sense creating, education policy for successful implementation.

The SEN teachers should have a major role in the development of a

SEN policy to promote effective inclusion an increased academic

performance of SEN students in inclusive settings, while Norwich

(2013) found low-self-esteem and question its ineffectiveness due to

inflexible curriculum is one of the issues of SEN provision.

Curricular changes are introduced in order to benefit students with

learning difficulties. This requires school staff, in particular

teachers, to be more reflective and analytical of their current

practice (Warnock et al., 2010). In general, the current situation

gives teachers neither the time nor the confidence to make a bridge

between the students in the mainstream, the Code of Practice (DfES,

2001) was being introduced to increase the flexibility of the

National Curriculum. However this flexibility is minimal (Ofsted,

2007).

Successful SEN includes: specifically trained professional

educators, special curriculum content, special methodology and

special instructional materials (UNESCO, 2010: 24). The

determination and coordination of headteacher, class-teacher, SENCO

and TAs in school general policy is vital and greatly influenced on

SEN provision. Additionally appropriate funds, resources, TAs’

support, regular and partnership of parents, school and Local

Educational Authority (LEA) boost SEN provision. Farrell (2011)

criticises inadequate resources, and funds for the SEN students,

low-payment for SEN teacher’s professional development and refresher

courses jamming this effective inclusion. Moreover most of the

schools rely on unqualified TAs or learning support assistants (LSAs)

who have no specific qualifications or training to support SEN

students (Ainscow, 2013). It entirely depends on school management

how effectively they use their TAs/LSAs.

METHODOLOGY

This study is based on qualitative research paradigm as multiples of

realities exist in any given situation by the individuals involved

in the research situation (Miles and Huberman, 1994). This is the

naturalistic/constructivist approach, also known the interpretative

approach or the post-positivist or post-modern perspective.

Semi-structured interviews technique was the tool chosen for data

collection according to the nature of enquiry and socio-cultural

constraints. The methodology for the interview data was content and

theme analysis, a technique that inferences by objectively and

systematic coding of the interview scripts into categories

(Chadwick, et. al, 1984). The school was randomly selected for nine

intensive interviews; headteacher, deputy-head, SENCO, teachers and

TAs. The small sample size was decided due to the small scale

project however it does not invalidate qualitative research because

issues raised and discussed in the interviews in order to focus more

sharply on the perceptions of the interviewees (Miles and Huberman,

1994). The interviews were coded according to respondents and

subject; HT; DH; CT1; CT2; CT3 SENCO; TA1; TA2; TA3; for reference

to identify the interviewees. The interviews were transcribed in

verbal and non-verbal thoughts of my interviewees.

Data Analysis and Discussion

The study explored three aspects of interviewees’ lives; their

personal beliefs, values and expectations; classroom experiences and

interpretation and professional training and its impact on their

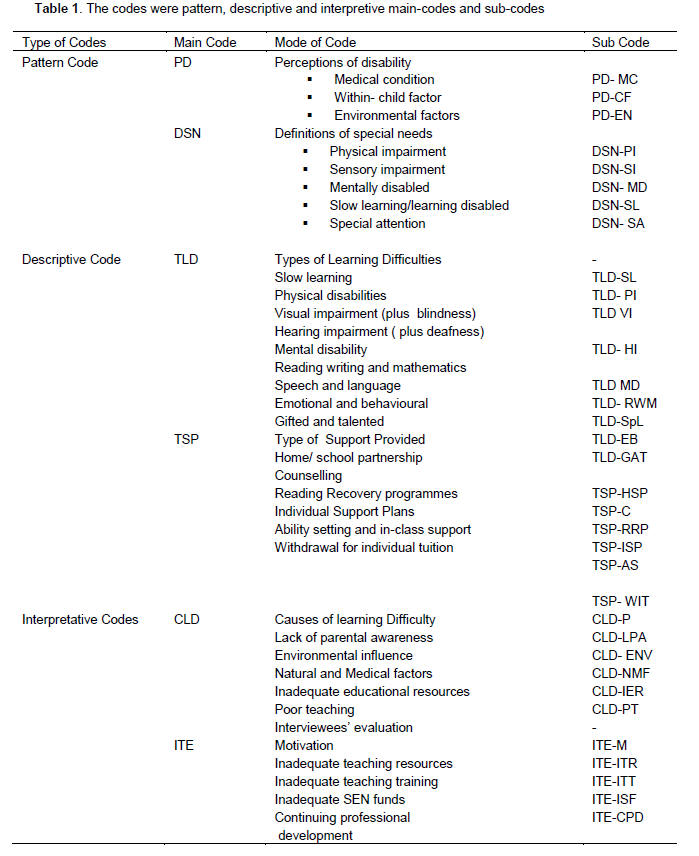

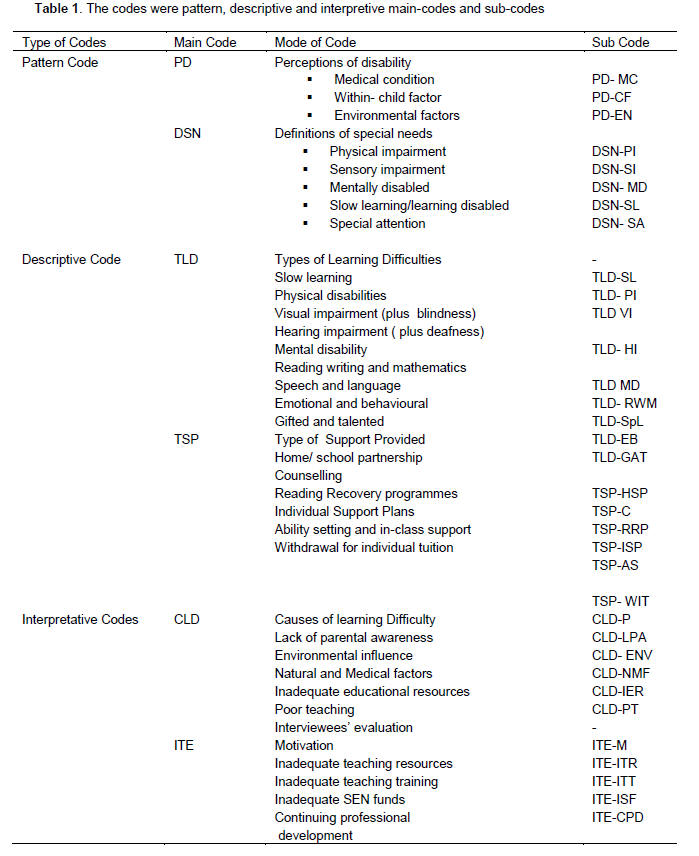

professional development. The codes were pattern, descriptive and

interpretive main-codes and sub-codes as shown in Table 1.

The pattern codes described the interviewees’ perceptions of

disability derived from their values and belief systems and

individual experiences. The descriptive codes described the types of

learning difficulties and support; the interviewees’ identified and

provided to the children that they considered the causes of learning

difficulties additionally their evaluation and provision of National

Curriculum and Code of Practice. Grouping the codes according to the

areas of agreements and exceptions, the following broad themes were

emerged;

1. The teacher’s perceptions of SEN

The teachers perceived disability in terms of medical conditions,

visible physical/sensory or mental conditions that required

medication and left permanent impairment. These were discerned

certain models of disability described by Sandow (2004), the

medical, magical and moral models respectively. Four interviewees,

explained disability in terms of a ‘within child’ syndrome or

nature.

It is in a child nature, when a child developed his/her nature then

none of the teachers can change it because nature does not

change.CT1. PD- CF .

A child nature could be moulded by

individual attention and conducive learning environment with his/her

peers, because learning difficulties might be a result of social

deprivation, parental indulgence, poor teaching and inappropriate

curriculum (Dyson, 2012). The interviewees

recommended special schools for severe SEN children.

2. Definitions of SEN

The definitions were based interviewees’ training, experience and

individual perceptions. These were combinations or influenced by old

and narrow concepts of SEN.

SEN children, who are slow learners or mentally/sensory

disabled/handicapped or need help during lesson. DH, DEF- SL, DEF-SI,

DEF- PI

However, the SENCO had understanding; It is a kind of support/help

for children who having any type of learning difficulty/ies. SENCO,

DEF-SATAs and teachers lacked of understanding their responses.

Their perceptions of SEN were contradictory, restrictive and narrow.

Although they agreed upon emotional and behavioural difficulties

affected child’s learning. Similarly Croll and Moses (2009) argue

that the mainstream teachers lacking awareness about SEN and its

provision that reflects through their lesson plans, class room

management and resources.

However majority of children experience

temporary learning difficulties which can be quickly remedied by

additional help from the class-teacher or with the assistance

specialist TAs and/or some curricular adaptations.

3. Types of Learning Difficulties

a. Slow Learning: (SL)

The sample referred slow learners as SEN students; These

children cannot go at the same rate so we arranged secluded class

for all subjects SENCO. TLD-SL

The slow learners always stay behind from their peers (Halliwell,

2011). Schools arrange this group or one-to-one support within

school hours. Halliwell argue that the content of the curriculum

should specifically design to meet the needs of SL with delayed or

seriously disrupted general development.

b. Reading Writing and Mathematics Difficulties (RWM)

The study found children with specific learning difficulties in

reading, writing, and mathematics:

Some students mostly girls, find science and mathematics are

difficult subjects. HT. TLD-RWM.

They considered these subjects as stereotypes that the boys are more

interested than girls. The school has a number of boys with learning

difficulties in these subjects. Most SEN arise from curricular

difficulties, such as gaining access to the curriculum or problems

in grasping and retaining concepts and skills in areas such as

English language, mathematics, science and the expressive arts. The

causes of such difficulties are most likely to lie in a mismatch

between delivery of the curriculum and pupils’ learning needs (Halliwell,

2011).

c. Speech and Language Difficulty (SpL)

The assumption for language difficulty was seen in terms of English

language because the school is situated in a mixed-racial cultural

population; lack of proficiency in English language is a major

problem, rather the children’s lack of proficiency in their

mother-tongue is more disturbing difficulty. HT TLD-SPL

Nevertheless, the Code of Practice (DfES, 2001:3) declared children

must not be regarded SEN solely because the language of their home

is different from the language in which they will be taught.

However, the teachers and TAs put them same category of SpL

difficulty;

They can’t read English reading books how their reading skill will

improve. CT1. CT2. TS2. TLD-SPL

However some schools have SpL units and therapist/specialist to

assess child’s SpL.

d. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulty (EB)

Bullying, aggression, disruption, withdrawal and restlessness were

some of the identified EB. Some teachers were keen to investigate

the causes with school councillor; I have pupils with certain

emotional and behavioural problems. Majority of these pupils from

broken homes, there main concern is poor concentration. CT1 TLD-EB.

SEN may arise from delays or

disturbances in emotional and behavioural development family life

which may affect the individual’s capacity to learn.

e. Difficulty due to Exceptional Ability (GAT)

The interviewees were eager to provide data of their GAT children;

These children are challenging if the work is not set according to

their calibre. CT3. TLD GAT.

There was good balance management of the class work; GAT

children are all rounders. We encourage them by giving more

challenging work not to feel them dejected. CT1. TLD-EB.

Thus GAT students were more challenging for teachers and TAs because

they have top set one group rather than specific GAT. Halliwell

(2011) recommended that the content of the curricular areas or

courses is expanded to ensure that abler pupils are suitably

stimulated and challenged to reduce their disruption. Most of the

interviewees were more comfortable, discussing general type

education issues rather than specific SEN issues.

.4. Types of Support Provided to SEN Children

a. Home School Partnership (HSP)

The interviewees emphasised the idea of HSP in addressing learning

difficulties.

We celebrate open days and invite parents to discuss about their

children plan accordingly. CT3 TSP-HSP.

However, Norwich (2013) dealt a comprehensive discussion about the

importance of home, school and LEAs relationship to make SEN

provision more effective. ‘The schools’ LEA failed in developing

successful co-ordination because only schools’ efforts are not

enough for successful inclusion,’ the sample complained.. Thus the

interviewees did not show any positive attitude to develop home,

school and LEA partnership.

b. Counselling (C)

The interviewees believed on counselling therapies to restore the

children’s self-esteem and confidence, thereby reducing/eliminating

children’s learning difficulties.

We have the facilities of school counselling for children with

emotional and behavioural issues. CT1. CT2. TSP-C

A child statement is the only required document that gives a picture

of his/her SEN. The LEA sends a child’s with statement and requests

the school counselling for support therefore most of the schools

rely on LEA’s statements only. Additionally Halliwell (2011)

suggests that the Individual Educational Plan (IEPs) should be

prepared with short and long term goal to be attained with

indications of: expected time-scale; approaches to learning and

teaching; assessment and recording; staff involved; resources;

learning contexts; and involvement of parents.

5. Special and Specific Intervention Programme

a. Reading Recovery Programme (RRP)

We have special intervention reading-classes under the supervision

of SENCO, teachers and TAs such as guided reading. SENCO. HT. TSP-

RRP.

We divided students in groups; gifted, advanced, average and SEN.

CT1 TSP-RRP.

However, it can be argued that the teacher will find hard to manage

four groups at a time because there are usually one TA per year. TA

job is to assure task completion and signed students’ Reading

Records (Ainscow, 2013). There is no proper timetable for Reading

recovery programme the students supported by SENCO or TA (Halliwell,

2011). Nevertheless this situation is varying from school to school

and their individual class room and staff management.

b. Individual Support Programme(ISP)

The school adopted ISP for specific subject learning difficulties.

We arranged separate booster sessions for SEN students like reading,

writing or mathematics and science. TA1. TA2. TA3. SENCO TSP-ISP.

This one-to-one support is very worth while for individual

improvement. The school had very positive response from the students

and their parents. It positively affected a child’s academic

progress. A child’s dependency is eliminated and a sense of

self-confidence and reliance and habit is developed (Halliwell,

2011).

c. Ability Setting and in Class Support (AS)

The teachers acknowledged that children learn at different levels of

achievements;

The class teacher allocates TAs for individual or group support,

sometimes in one lesson there are 2 to 3 TAs. HT. SENCO. TSP-AS.

The teachers allocate TAs according to the needs and abilities of

the children. However (Ainscow, 2013) criticised that the mainstream

schools over or misuse their support staff because most of them are

inexperienced and unqualified for SEN support.

d. Withdrawal (WIS)

Withdrawals of students from classroom make the classroom management

easy for teacher. However; withdrawal students are supported

by TAs in a reserved room. CT1. HT.DH.WIS

This constant withdrawal of SEN students put negative impact on

their learning, sharing and team work abilities (Halliwell, 2011).

To minimize this practice an effective lesson plan is vital with

combinations of varieties of tasks according to the calibre of SEN

students within the classroom. Although very few SENCO support

class-teachers in lesson planning their main focus are SEN support (Ainscow,

2013).

6. Causes of Learning Difficulties

a. Lack of Parental Awareness and Lack of Interest (LPA)

Lack of parents’ involvement and interest in their child’s education

is the main cause of learning difficulties they always complaining

lack of time and other engagements.

Most of the parents do not understand the importance LPA in their

child education. They always lacking of time and even don’t turn-up

on parents-meeting. HT. DH. CLD-LPA

The rights and responsibilities of parents should respected and they

are actively encouraged to be involved in making decisions about the

approaches taken to meet their children’s SEN. Parents can do much

to support the work of the schools when the teachers involve them in

assessing and reviewing SEN; making decisions about the content of

the curriculum; and monitoring and reporting on progress as observed

at school (Dyson, 2012). However, sample teachers and TAs were

disappointed with parental response.

b. Environment Influence Peer-group

Pressure (ENV)

Children home and social environment contribute a significant role

in pedagogy;

Peer groups and environment affect the child’s performance and

ability. CT3 CLD ENV

Home and social environment have positive or negative effect on a

child’s abilities usually children from split families have negative

impacts. The study found more negative aspects in terms of parental

attention and interaction with students’ families.

c. Inadequate Provision of Educational Resources (IER)

The interviewees complained about lack of educational resources to

prepare their lessons.

Sometimes the borough delays the provision of resources, or the

school lacks funds. HT. CLD IER.

This is one of major issues now that LEAs have failed in the

provision of teaching and learning resources to schools on time (Ainscow,

2013). As a result, the school has struggles for an effective SEN

provision. There was an impression among the teachers and TAs that

it is the responsibility of the head and deputy to make this supply

possible in time.

e. Inadequate SEN Funds (ISF)

ISF obstructed the way of successful SEN provision.

First we were getting individual SEN funds per child but now it is

for the school therefore its insufficient for SEN students. HT, DH,

SENCO, CLD-IER

However, the concerned school’s LEA mostly delays the provision of

funds and resources that causes ineffective SEN provision and

management (Ainscow, 2013). Both the head and deputy were not happy

with the present allocation of funds, resources and revised polices

of its provision. The government revised their strategies due to

increased number of SEN students every year. The interviewees were

in favour of individual SEN student funds. Frederickson and Cline

(2009) further supported the argument that teachers in the

mainstream are confident in their ability to implement inclusion

effectively. Nevertheless, the main barriers are the inadequate

funds and educational resources.

f. Poor Teaching (PT)

A poor teaching methods increase children’ learning difficulties.

The system could be developed to raise the profile of the

profession, increase professionalism and competency and ensure good

practice.

A lesson is interesting, no matter how dull the child is there will

be an aspect of lesson that a child enjoyed. CT1, CLD PT.

The sample school has all qualified teachers. There is no proper

arrangement for their training or refresher courses to introduce

them to the new strategies and techniques to make their lessons more

interesting for SEN students. Their lesson plans mostly rely on the

availability of material and their knowledge. The teachers had PGCE

or GTP without specific SEN qualifications. Similarly TAs had no

proper training and qualifications only few have considerable

experience working with children but not with the SEN exclusively.

Schools rely on TAs for SEN provision (Ainscow, 2013). Interestingly

the school avoid hiring a supply-qualified teacher in teachers’

absence they give the class under the supervision of unqualified TA

or split the students into groups (5-7) and send them to different

classrooms.

6. Teacher evaluation and Implementation of National

Curriculum/Code of Practice

The National Curriculum and Code of Practice affect teaching

practice. In this regard, a theme that constantly emerged in all

interviews was that of teacher motivation, resources availability,

teacher training curriculum, funds for SEN students and professional

development. Most of the teachers were interested in the SEN

classroom arrangement and SEN lesson plans.

We need workshops and seminars and refreshers courses to merge Code

of Practice in National Curriculum. CT1 CT2 CT3 TA1 TA2 TA3, ITE-CPD.

Golder et al., (2009) recommend teachers in-service training

regarding necessary understanding and skills for SEN provision to

make a bridge between the National Curriculum and Code of Practice

for an inclusive setting. Therefore teacher-training curriculum in

colleges/universities should be revised to include generic broad

based SEN as a compulsory element in initial teacher training.

Further tailoring of the curriculum to meet individual needs is

possible through a degree of flexibility within programmes to enable

students to select subject areas of individual relevance.

CONCLUSION

This study concluded that teachers do not regard the SEN that helped

in identifying children with special needs. The study theorise lack

of funds, resources, SEN trained staff and partnership between

parents, school and LEAs blocking the effective provision of SEN.

Additionally it is vital to involve SEN qualified teachers from

mainstream for an effective review of inclusion policies and

practice. They are the real means or policy makers for the

evaluation and review of existing polices to be effectively

implemented in the mainstream. Every policy has been judged by its

effective provision in practical environments. Because we have to

start asking what is wrong with the school rather than what’s wrong

with the child!’(Ainscow 2013:17).

This small-scale research study has limited scope of generalisation

because the qualitative data analysed does not allow many strong

conclusions regarding differentiating the various SEN issues

described here. The sample hardly interpreted an accurate picture of

the present situation of policies and practices. Inclusion

represents a complex system of education and need more time and

practice to absorb each other. However, it may be concluded, that

inclusion has not gained much ground in the country since the mid

1990s, it seems that SEN needs more practical reforms and policy

organisation. Educational segregation provision in mainstream

presented mixed views, that a gradually increasing number of parents

want their children with SEN to attend a regular school.

Furthermore, inclusion requires a rethinking of the role of SEN in

mainstream; why some students are failing to learn, and the teachers

fail in effective teaching. The present polices of the schools are

mostly theoretical and formal documents. Overall, the research found

no evidence in the school of systematic discrimination or

unfavourable treatment of students with SEN in the classroom setting

or in admissions process. For students with SEN there were no

statements, schools simply did not have an opportunity to do this,

as information about pupils’ abilities and needs was not available

when the admissions criteria were being applied. All schools

respected the legal position of SEN students and arranged special

provision for such students. To conclude this discussion both

opponents and proponents of SEN can find scattered research to

support their respective views, since the current research is

inconclusive. Opponents point to research showing negative effects

of the provision of SEN, often citing low self-esteem of students

with disabilities in the general education setting and poor academic

grades. For those supporting inclusion, research exists that shows

positive results for both special and general education students,

including academic and social benefits. Currently, the issues of SEN

appear to be under discussion. The practical definitions of

government polices supporting the practice, schools need to continue

their search to find out the ways to include SEN students in the

mainstream schools successfully.

REFERENCES

Ainscow M (2013). From special education to effective schools for

all in: Florian, L. (Ed); The Sage Handbook of Special Education;

Sage Publications London (SPL); pp. 146-159.

Chadwick A, Bahr M, Albrecht L (1984). Social Science Research

Methods; Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Croll P, Moses D (2009). Pragmatism, ideology and educational

change: the case of special educational needs. British J.Edu.

Studies. 4 (6):11-25.

(DfEE) Department for Education and Employment, (2001). Code of

Practice on the identification and the Assessment of Special

Educational Needs; DFEE, London.

(DfEE) Department for Education and Employment, (1994). Excellence

for all children: meeting special educational needs; DfEE, London.

(DfES) Department for Education and Skills, (2001). Special

Educational Needs Code of Practice; DfES, London.

Dyson A (2012). Special educational needs and the world out there

in: Contemporary Issues in Special Educational Needs. Open

University Press London (OUPL); pp.13-27.

Farrell P (2011). Special education in the last twenty years: Have

things really got better. British J. Sp.Edu. 28 (1): 3-9.

Frederickson N, Cline T, (2009). Special Educational Needs,

Inclusion and Diversity: A Textbook; Open University Press, London.

Golder G, Norwich B, Bayliss P, (2009). Preparing teachers to teach

pupils with special educational needs in more inclusive schools:

evaluating a PGCE development. British J. Sp.Edu. 32 (2): 92-99.

Halliwell M (2011). Supporting Children with Special Educational

Needs; David Fulton Publishers London.

Legislation and Guidance in relation to SEN (2005-06) http://teach.newport.ac.uk/sen/SEN0405/Law/Legislation0405.htm(Retrived

7/1/13).

Miles B, Hubermen M (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage

Publications London.

Norwich B, (2013). Addressing tensions and dilemmas in inclusive

education: living with uncertainty; Routledge London.

(Ofsted) Office for Standard in Education (2007). A survey of the

provision in mainstream primary and secondary schools for pupils

with a statement of special educational needs related to specific

learning difficulties; Ofsted London.

Sandow S, (2004). Whose special need? in: Sandow S, (Ed). Whose

Special Need? Some Perceptions of Special Educational Needs; Paul

Chapman Publishers London (PCPL); pp. 153-159.

UNISCO Report, (2010). http//:www.unisco/report.html/0000 231 (Retrived

7/1/13).

Warnock M, Norwich B, Terzi L (2010). Special educational needs: a

new look; Continuum Publishers, London.

|