|

|

|

International Journal of Political

Science and Development Vol. 1(2), pp. 32–41,

October, 2013

ISSN: 2360-784X©2013 Academic Research

Journals

Review

Governing Mechanisms for Controlling Labour: The case of the

Ready-Made Garments Industry in Bangladesh

Kazi Mahmudur Rahman

School of Political Science and

International Studies (POLSIS), University of Queensland, St Lucia,

QLD 4067, Building 39A (General Purpose North), level 5. E-mail:

kazi.rahman@uqconnect.edu.au

Accepted 9 October, 2013

Dominant discourse of

trade led development justifies the treatment of workers by

subordinating their needs to the overarching imperatives of

development. The official transcript of Ready-Made Garments (RMG)

trade induced development is interpreted as progress, while for

workers it is associated with the decline in the quality of life and

as forms of suffering and even as enslavements. Based on a field

survey on workers, in-depth interview on factory owners and

observation, this article also provides an account of the political

power relations underpinning the “worker/employer” constellation in

the RMG sector in Bangladesh by investigating the formal and

proto-formal arrangements/provisions. Since labour power is a

critical input into RMG Industry (RGI), this article also identified

the various modes of labour control in the RGI in Bangladesh. The

analysis also shows the efforts in legitimizing those controlling

practices. The core of this paper is an exposition of the governance

mechanisms through how the new international division of labour (NIDL)

wassustained despite the worker’s struggles. At the end, it

envisages to expose the gap between stated governance objectives and

governance as experienced.

Key words: Ready-Made Garment (RMG), International Division

of Labour (NIDL), Trade and Governance, Labour Relations, Labour

Rights, EPZs.

INTRODUCTION

A number of national as well as international development commentators

conceive of ready- made garments industry as an ‘aashirbad’ (blessing)

for countries like Bangladesh in general, and for women workers in the

RMG industry in particular. For example, Jeffry Sachs conceives of

sweatshops within the RMG sector (and in Bangladesh in particular) as

the route to progress; “sweatshops are the first rung on the ladder out

of the extreme poverty” (Sachs, 2005; 11). Similarly, Bradsher (2004)

has identified this development as advancing a silent revolution in

Bangladesh with significant social and cultural benefits for women. This

progressive narrative of trade-led development relies on two arguments:

competition and development where nation-state is transformed into a

competition state in order to streamline development. As such, countries

like Bangladesh are competing to register their superiority in exporting

ready-made garments in the world market. It also argued that introducing

competitive forces into the economy will accelerate development. Donado

and Walde argue that to achieve the associated transformation of the

political economy poor countries must reduce and reconfigure labour

standards to attract investment and remain competitive (Donado and Walde,

2012). Therefore question remains whether workers’ rights are respected

in ways commensurate with this discourse of development. And hence, the

present work contend that dominant discourse justifies the treatment of

workers by subordinating their needs to the overarching imperatives of

development.

In contrast to the traditional orthodoxy of development notion, Saurin

(1996) argued to develop a holistic method of measuring development

which would take account of people’s perception and understanding of

that production and reproduction of their own lives, including the

global structuring of production and reproduction (Saurin, 1996; 661).

Her approaches aim to track the development or non-development of the

lives of ‘ordinary people’. She used James Scott’s (1990) notion of

‘Public and Hidden Transcript’ in different way. Official account of

development is expressed in broad terms such as economic growth,

international competitiveness, expansion of trade and rapid trade

liberalisation and regulation of interdependence (Saurin, 1996; 661).

However, daily experience of working people, their structural

transformations, dislocations and sufferings fails to correspond with

official story of development’ (Saurin, 1996: 662).

Consequently, the transmission of trade-led modernity is interpreted as

development and progress, while for others it is associated with the

decline in the quality of life and as forms of suffering and even as

enslavement. The persistence of workers suffering as demonstrated

through low wages and deprivation from their rights contradicts the

putative modernity of this discourse. The present work attempts to

illustrate how formal institutions and informal mechanisms interact to

produce the working conditions in the RGI in Bangladeshand also

articulate how dominant public narrative of ‘development blessings’ is

constructed through using various labour controlling mechanisms.The

interactions between these institutions and mechanisms comprise a

“governance” structure that effectively disempowers workers, leaving

them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

Indicators of disempowerment and exploitation include insecure

contracts, low wages, excessive hours, and few benefits. However, actors

(state and stakeholders that includes private trade association and

trade union leaders) concerned with the RGI have tended to refuse to

recognize their suffering and instead have resorted to the use of both

force and developing mechanisms to acquire consent from the workers (and

within society) to maintain this favourable export situation. Since

labour power is a critical input into every commodity chain, the

following work also seeks to identify the various modes of labour

control in the RGI. The analysis also shows the efforts in legitimizing

those controlling practices. At the end, it envisages to expose the gap

between stated governance objectives and governance as experienced. In

order to do so, this article the present work has adopted a systematic

narrative, which comprised with a multi-sited investigation based on

in-depth interviews and close observations .

This present article is divided into three sections: the first section

briefly outlines governance mechanisms in the RGI in relation to both

labour rights and investors’ protection. This section attempts to show

how labour rights and regulation can only be adequately comprehended

understood through an appreciation of the national and global

transformations. The second section delineates how the formal and

informal mode of governance plays out as a strategy to manage the

contradictions between trade-led development and workers struggles. It

shows that this strategy is consisting of both the use of force and

consent. The third and final section highlights how this governance

deficit has been legitimized by various stakeholders despite the

workers’ suffering.

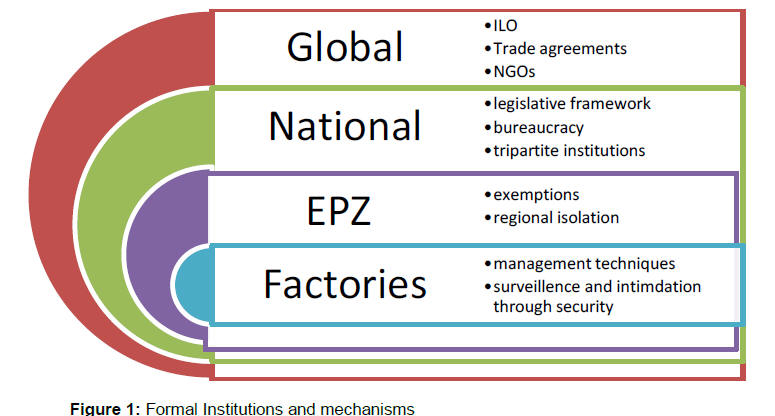

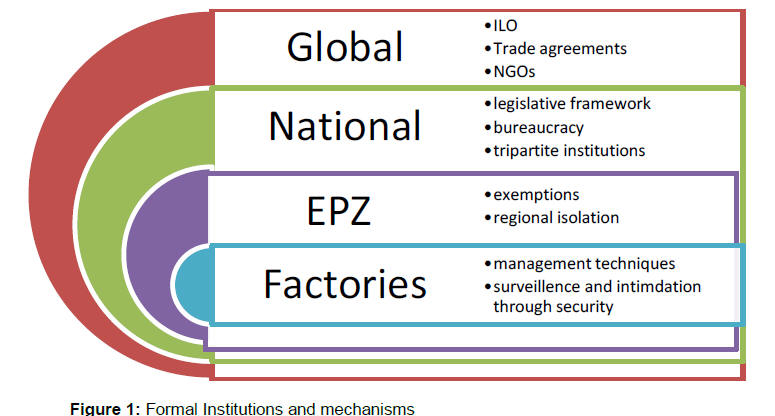

Section 1: Formal Institutions and mechanisms in the RGI in

Bangladesh

Various institutional mechanisms generate the ultimate goals of creating

subordinating workers (or rather exercised their limited capacity to

address workers sufferings) for their needs to the overarching

imperatives of development. The Figure 1 illustrates these institutional

measures addressing workers right operates in global, national, Export

Processing Zones (EPZs) and non-EPZ factory level.

While discussing labour rights perspectives, the first global platform

for monitoring labour’s right is the international labour organisation (ILO).

ILO has been using their programmes under the heading ‘decent work’

which promotes four core labour standards . It supervises compliance

with global labour conventions and publishes reports on violation on

maintaining standards. It provides technical assistance to labour

ministries and other agencies. In theory it can punish countries

(according to Article 33 of ILO) that do not comply with their

commitments. However, in reality there are hardly any examples of such

(Elliott, 2003). It provides the only functioning supervisory mechanism

which is central to the international legal arrangements for labour

standards.

Along with the ILO’s supervisory context, the global regulatory regime,

particularly the code of conduct and standards manifest the chain

prerequisites of the RGI. The origination of buyer’s code of conducts

was not proactive rather it was reactive. In response to the threat of

scandal and to reputation, brands and retailers introducing introduced

ethical codes of conduct that specify labour standards that the

supplying factories producing their orders ought to maintain. Global

buyers fear that trade unions, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs),

human rights groups, and consumers’ associations in developed countries

may accuse them of encouraging their suppliers in developing countries

to run sweatshops and use child labour. To avoid such accusations, they

urged local suppliers (garments manufacturers) to follow codes of

conduct regarding product safety, labour standards, working

environments, and child labour issues (Humphrey and Schmitz, 2004).

Codes may have had a number of important impacts (like banning child

labour or improving factories toilets), but it is not evident based as

regard to their role as a sole monitoring agencies of the factories

(Brooks, 2007: 173). Since, observation and in-depth interview with the

factory owners in Dhaka revealed that both the buyers and local

manufacturers are still outsourcing their orders to the sub-contracting

factories where those factories lack basic labour standards. Apart from

these flexible global initiatives, the national government also

introduced a number of private enterprise friendly policies and

legislation.

From the 1980s, in order to facilitate the expansion of the private

sector led development and attract direct investment (FDI), government

adopted a number of policy initiatives. To stimulate investment,

framework for FDI policy is based on two legislations; the Foreign

Private Investment (Promotion and Protection) Act, of 1980 and the

Bangladesh Export Processing Zone Authority (BEPZA) Act , 1981. While

the first defines the scope and space for FDI in Bangladesh, the latter

specially addresses the provisions for FDI in the EPZs. One of the

important features of this policy is to protect the investors both in

terms of securing their financial assets and allowing exemptions from a

number of certain legal provisions.

Protection against expropriation of foreign investors has been

guaranteed in the Foreign Private Investment Act of 1980 where

provisions for adequate compensation was laid down. If a foreign

corporation becomes a subject as a legal measure that has the effect of

expropriation, provision for adequate compensation has been kept and

foreign investors are allowed to repatriate capital to their home

country. The policy also includes a number of fiscal incentives. They

include tax holidays for the industries located in free trade zones (3 –

7 years, depending on their location); reduced import duties on capital

machinery and spare parts; tax exemption on royalties, and on capital

gains from the transfer of shares and duty; free storing facilities

(bonded warehouse) for imported goods. It also allows for certain

infrastructural incentives, which include space in the EPZs and a

relatively lower price of land in industrial estates with electricity,

gas, water, and sewerage.

EPZ has been characterized from the very beginning due to its dubious

legislative framework (the right to freedom of association often do not

apply in EPZs , isolation from other factories (Dannecker, 2002),

reactive rather than proactive (factory visits on ad hoc basis), denial

of access (denied access to EPZs when carrying out enforcement visits

without prior notice or prior authorization) and low levels of dialogue

(since trade unionization is prohibited) . To attract the foreign direct

investment the government had started campaigning to the international

community that 'there are no trade unions in EPZs' (EPZ, 2000 ). Even

the recent EPZ’s advertisement under “Why Invest in Bangladesh EPZ?”

didn’t mention the trade union rather mentioning about the benefits of

smooth law and order and low cost production base amongst the Asian

region. This also reflects the government campaign to promote EPZs in

particular and country’s FDI in general as the Minister for Industry was

more categorical in saying, “the prime objective of the government is to

increase employment opportunities through increased investment. Any

issue relating to EPZs of Bangladesh should be considered cautiously” (Siddiqui,

2001: 1 ).

National legislation also provides safeguards for the workers and it

stipulates the following conditions: wages and benefits, employment

condition and workplace safety, working hours. Bangladesh Labour Act (BLA)

2006 took effect from October 11, 2006. According to the US Government,

the BLA 2006 is the most comprehensive law in place regarding labour .

This indicates the central progressive narratives and justification that

RGI mechanism is adequate in the question of labour rights’. However, a

number of the incidents of labour unrest occurred due to lack of

implementation of Bangladesh labour Act 2006 . Despite these legal

provisions, workers suffered due to non-implementation of these

provisions (60 percent workers endorsed ) and workers couldn’t address

their grievances due to non-existence of unions (85 per cent workers

endorsed). Unionization efforts in the non-EPZ factories are not that

different in practice compared to the EPZ. The Bangladeshi Constitution

and the 2006 Bangladesh Labour Act provide for the right to join unions

and, with government approval, the right to form a union . However, many

restrictions apply which effectively undermine rights to freedom of

association, to collective bargaining, and the right to strike. This is

quite significant and contradicts with spirit of trade unionism and it

implies that law itself was created to impede the formation of unions.

Analysis of national governing institutions for implementing and

overseeing labour rights is important. Government institutions also

suffer from serious under-capacity, particularly the Ministry of Labour

(MoL), which is understaffed and lacks the resources to adequately

inspect and carry out its mission . The Ministry of Commerce (MoC) is

also extensively involved in labour governance in the export sector.

While the primary function of the MoC is to deal with trade and

commerce, both externally and internally, compliance issues have also

become an important part of the MoC’s portfolio due to its potential

impact on exports. In addition to this forum, the government has also

created three related groups: a taskforce on labour welfare, a taskforce

on occupational safety and health, and a Compliance Monitoring Cell

(CMC) which is run out of the Export Promotion Bureau . Therefore lack

of inter-ministerial coordination and lack of consensus on working for

worker’s rights creates problems within the government institutions.

One of the prominent governance processes in the RGI is the creation of

the industrial police (IP), which is a specialised police force

established to look after industrial areas. It came into operation on

31st October, 2012, with headquarters in Dhaka and four zone offices at

Gazipur, Saver, Narayanganj, and Chittagong. The five objectives of the

IP state the following:

“(1) to ensure the law and order of the industrial areas; (2) to ensure

the safety and security of the property and personnel involved in the

industries; (3) oversee the activities of the organized groups working

to destabilise the industrial sectors; (4) extend immediate support to

any unusual situation/labour unrest; and (5) collect, collate and

disseminate information to higher authorities.” (GOB, 2011)

Interestingly, no indication appears in the five objectives of IP that

this force aims to safeguard the interest, insecurity, deprivations of

the workers, or any sort of violation of labour laws. Even during my

fieldwork, especially during a situation of unrest in a factory (that

is,

in Tejgaon in Dhaka in August, 2011), the industrial police mostly

protected the factory and the owners, rather than the workers. Some of

the workers stated that on a number of occasions, just before their

payment date, they observed the presence of industrial police, and,

subsequently, they heard about the closure of factory . They narrated

that “this is a method by the management so that they could delay

payment and could earn interest depositing money in the bank” . An

in-depth interview with an industrial police on the spot also revealed

that management instructed them to save or protect the factory first and

concern themselves with any issue regarding the workers until later.

Major governing institutions the factory level are the two association,

Bangladesh Garments Manufacturer Exporters Association (BGMEA ) and

Bangladesh Knit Export Manufacturers Association (BKMEA ). These

associations are clearly sensitive to international pressure and to the

demands of buyers in the area of labour compliance. The employer

association primarily active to respond the buyers concerns rather than

the concerns of the workers. Since the proposed Harkin Bill of the

mid-1990s (to eliminate child labour), the BGMEA, BKMEA, have begun to

institute a variety of programs designed to improve working conditions

in order to burnish their reputation in the international marketplace.

The private business houses have their own intelligence units. Both

BGMEA and BKMEA are equipped with their own security and intelligence

units. Now-a-days factories (a number of big compliant factories) also

have their own trained security personnel.

One way of governing inside factories is through the ex-military

management. A large number of factories are run retired army, navy or

air force officers. According to one of the manager, in a factory in

Ashulia (near Dhaka), “since workers are uneducated, unorganised and

easily manipulated, they would require the strict rules. These rules and

verbal (loud voice commands) control make them equipped with this new

working set-up.” These former army personnel often verbally abuse the

workers and, a number of them; physically punish the “disobedient” ones

. Therefore, RMG employment not only provides employment opportunities,

but also rectifies the workers attitudes.

This section outlines various institutional and regulatory measures

which operate in global, national, EPZ and factory level. However,

analysis shows a number of weaknesses which can be broadly attributed to

their weak institutions and cumbersome legal provisions. It also

revealed the elements of force in the maintenance of ultimate governance

mechanisms in the RGI. It is important to know about implications of

those regulatory and institutional measures. I argue that these measures

have been governed by management through surveillance and intimidation

tactics to disempower workers. The following section outlines these

management techniques.

Section 2: Managing Governance Strategies

Managing code of conducts

While discussing the codes of conduct, the buyers’ preferences for their

own codes of conduct pose a challenge for the suppliers. One supplier

usually has more than one buyer. If each buyer has a different set of

requirements, it becomes difficult for the local garments manufacturers

to ensure compliance with all the requirements simultaneously, although

direct suppliers are often in a better position than sub-contractors to

meet expectations. Suppliers are regularly monitored to ensure

compliance, however, small and medium size factories, which usually

include subcontractors, often fail to comply with the code of conduct.

However, the total approach of their monitoring is focussed on industry

specific competitiveness or goals (that is, improving competitiveness,

fire and safety standards, and so on) rather addressing the workers’

grievances or suffering. Moreover, monitoring is generally ad hoc (Rahman

et al, 2008). Both NGOs and trade unions have criticised monitoring

activities because there have been examples of monitoring agencies

certifying factories lack safety standards working facilities (Brooks,

2007). The auditing mechanisms were constructed in such a fashion that

both the parties (the garments manufacturer and the audit house) were

uninterested in addressing the workers grievances. Buyers cancelling

orders placed with manufacturers (with whom they had long standing

relations) who had not maintained standards was rather uncommon . In

most cases , auditing firms) refrained from expressing their

dissatisfaction (because of the feared of losing their job) or being

trained not to express their dissatisfaction, or the audit firms failed

to properly investigate the non-fulfilment of standard requirements.

Controlling workers’ wages and benefit

The RGI is composed of an unseen, intricate, and complex web of supply

chains that run like invisible web around the world. These chains have

been structured to gain low-cost, low-risk, and flexible production in

an increasingly competitive environment. The payment for their work was

often below overtime rates, frequently late, and sometimes unpaid.

Workers had to work overtime, either because the management wanted them

to do so, or because they were slow in finishing on time, or because

they would require extra overtime payment for their daily survival. Non-formalisation

is another aspect of how manufacturers govern the RGI industry. In

Bangladesh, a number of workers had no contract or employment letter.

Though a number of factory owners claimed that they provided with the

workers with a contract letter, in-depth interviews of workers revealed

a different story where the garments factory authority provided the

workers a one page contract letter while joining. However, they took it

back that so that they could use the document for other workers.

Without contracts, this meant that they were ineligible for certain

legal entitlements. Though popular discourse about formal employment

through RMG trading is something very common, in reality they themselves

make this employment more in an informal manner in order to create a

flexible space for governing the workers.

One of the central pressures that the workers faced is the management of

low wages.Common problems surrounding wages were that wages were low,

late, incomplete, and sometimes complex to calculate. Wages were often

purposely made complex, so that workers could not calculate their wages

in advance and did not know if they had been underpaid. Sub-contracting

factories usually received lower payment. A number of factories, did not

pay the full monthly salary, attendance bonuses (or even festival

bonuses), overtime payments altogether in one day. Some of the owners

argued, that “if they were given full payment, they might not come back

to the factory and would go to another factory, they might misuse the

money, or might have face problems carrying this ‘huge’ sum of money” .

Managing workers’ protest and unionisation efforts

There have been reports with regards to increasing pressure on workers’

unionisation efforts. In-depth interviews, anecdotal information, and

close observations reveal that that government and employers are

becoming increasingly hostile towards trade unions. This has also made

workers reluctant to join trade unions where they do exist. Trade unions

were under pressure internally because of corruption and workers

perceived some unions to be working to support the employers rather than

the workers. A number of trade unions also become more affiliated with

both ruling and opposition political parties (Majumder, 1997: 49);

hence, the political power, rather than the workers, became their

primary interest. In Bangladesh, workers involved with trade unions

faced redundancy, harassment, and intimidation, as well as being

threatened with murder. Very recently, this threat was carried out;

Aminul Islam, a prominent trade union leader, was killed . However,

anecdotal evidence suggests that a number of factory management

considered him as to be a threat (due to his voice against the factory

owners controlling mechanisms) to the industry as a whole. The

government is still investigating the matter. Again, all these

activities or narrow governance mechanisms focused on creating

deterrents so that other workers will not act against factory

management.

Section 3: Legitimisation of the governance process

The earlier section exposed the governance mechanisms applied through

force and consent. However, recognition of regimes of abuse and control

in globalised production sites of the RMG has been legitimised by state

and non-state actors. There is recognition of justification- even when

countering critique and thereafter a range of justification emerged.

These examples of abuse are both grounded in and reproduce a large

political economy of production, consumption, and image-making.

Construction of workers’ social obligation: the use of power and

conspiracy theory

The most prominent and common feature of legitimization efforts can be

traced through the hyped “conspiracy theory” outlined not only the

factory owners and private trade association but also the government.

The government’s responses to the protests have generally entailed a

combination of coercion (for instance, arresting protesters) and

attempts to re-vitalize and consolidate the dominant discourse about the

benefits of the RGI. In the case of the latter, the fact that the

protests could reflect the genuine grievances of the workers was either

dismissed out of hand, or deflected by framing the protests as part of a

larger (foreign backed) anti-government conspiracy that private business

bodies, NGOs, and foreign governments had instigated.

In terms of direct coercion, the government has responded drastically to

the workers’ protests in an attempt to discipline those labeled

“so-called provocateurs” with the help of the “industrial police” . The

“industrial police” force came into existence on July 31, 2010 when the

Bangladeshi Prime Minister warned that “the government will not tolerate

any anarchy and destructive activities in the garment sector”, promising

that “tough action would be taken against the people who are creating

anarchic situation in the garment sector” (Daily Star, 2010) . The

coincidence of interests between the government and manufacturers is

perhaps, in this case, unsurprising. Irrespective of shared ideological

commitments to development as modernization, the government itself has

much at stake in the RGI (McMichael, 2010). For example, twenty-nine

Membersof Parliament (MP) in Bangladesh are owners in the garments

industries (10 per cent of total MPs) and another 25 percent are

indirectly involved with this industry (Bangladesh Election Commission,

2009 ). This indicates the government-business compact has arguably had

the effect of diluting state responsibility for protecting workers from

the violation of their rights.

Management consistently discusses workers in disrespectful terms – ‘son

of a beggar’, ‘workers would go strive if they would not employ them’.

This analysis suggests that workers are discursively constructed as not

deserving of rights, an analysis that could work to further justify

working conditions. How words become a part of dominance becomes evident

through the governance process of the RMG industries. While visiting RMG

factories in Narayanganj, one of the factory owners was quite annoyed

with the workers (particularly on those who were involved with the

protest), because he said “fakinnir put” (son of a beggar) would

struggle (go strive) if they would not employ them. On a number of

occasions, garments owners claimed that “it is the owners who provide

bread and butter to the workers and ultimately provide employment and

facilitate poverty reduction.” This is the justifications for the

workers conditions. This section discusses two examples of how the

identity of workers as dependent on the largesse of the manufactories

and as individuals whose rights ought to be subordinated to more general

development goals: 1) re factory shutdown and 2) recent debate over

maternity leave provisions.

The latest show of power and domination was by the garment factory

owners who at first threatened (on June 03,The Daily Star, 2012) to shut

down their factories (subject to sustained worker protest) and, later

on, shut down the factories of the entire Ashulia region (which has more

than 300 factories) for five consecutive days. Anecdotal information

suggests that the owners lost 20 million dollars (USD) ( Ahmed

Salahuddin, 2004) during this closure, which would be the equivalent to

giving the workers, had they wished to do so, a five per cent salary

increase. This appears (or should be) a quite depressing scenario for

both the owners and the workers. However, the owners were quite happy to

give the workers a lesson and the workers suffered quite a

lot—especially those working in piece-rate basis. One of the garment

factory owners who visited Australia in June 2012 (during five day

factory shut down) said the following:

“I am not worried about my loss that occurred during this shut down, as

I have got other businesses. It is a good way to teach workers and in

future they will think twice before going into another round of

protest.” (Interview with an owner of RMG factory).

The second example regards maternity leave, which further revealed the

factory owners’ perception. This as a structural phenomenon (socially

constructed knowledge) linked with the patriarchal cultural

construction. Bangladesh Garments Manufacturers and Exporters’

Association (BGMEA) has argued that the proposed 24-week maternity leave

instead of 16 weeks, will encourage a higher birth rate, negating

population control efforts in the country. The association also proposed

introducing 12 weeks or 84 days of maternity leave for female workers in

the garments industries to keep pace with production in the sector. In a

statement, BGMEA said that the industry had been contributing to birth

control in the country since the 1980s because female workers felt

discouraged from having children in order to keep their jobs. They

further proposed that because 80 per cent of workers in the garments

industry are women, their long leave would greatly hamper production and

increase administrative complexity if recruiting the new workers to fill

the vacant position. In addition, a long absence decreases workers’

skills and workers could also not return to work if they found a better

opportunity elsewhere . The BGMEA’s stance of reducing maternity leave

from a commercial viewpoint defames Bangladesh’s women (Nazneen et al,

2011), children, and the community and disgraces future generations.

However, this sort of structural construction has been intuited with

other institutional force.

Educating responsible behaviour of the workers

Garments manufacturers often assumed that people who work in factories

lack basic intelligence, because they lack a proper education and have

insufficient mental capacity. Therefore, in the RGI, a principle of

combining standardization of production practices, such as the

break-down of work task on the assembly lines, has been very prominent.

Further to these production strategies and after a series of protest

during 2010 and 2011, a number of programmes to teach “responsible

behaviour of the workers” have been inaugurated in Bangladesh in

collaboration with the donors, NGOs, and business bodies. The basic aim

of these programmes is to make them disciplined (or bring them under

control), because a number of them become agitated when they were dire

deprived. GiZ (German Development Cooperation Agency), with the

collaboration of two local partners, the Bangladesh Knitwear

Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA) and Bangladesh garments

Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), has funded one of these

programmes, Promotion of Social, Environmental and Production Standards

(PSES). The programme aims to introduce social and environmental

standards, and models of arbitration. The programme’s ultimate aims has

been designed in a manner as “the only way for the industry to remain

competitive in the long term, while maintaining humane social standards

and environmentally sound production methods” (GiZ, 2011 ). Two of the

national NGOs, Awaj Foundation and Karmajibi Nari acted as local

partners by organising awareness-raising workshops and distributing

information in the factories. PSES claims that women received higher

wages and BKMEA member factories have improved their productivity by

around 33 per cent on average. It also claims that in some cases labour

productivity has doubled. However, an in-depth interviews with both with

the project coordination officer and beneficiaries’ (workers) reveals a

different perspective. The design of their model of arbitration

programmes is such that they trained workers about their behaviour

during protests. This includes, not stopping work, not being involved

any sort of destructive activities, and not getting out of factories.

This illustrates the ultimate intention of the controlling mechanisms of

the RGI.

Legitimisation through cultural modernisation loops

Over the last couple of years there have been renewed attempts to

promote cordial relations between workers and management through

participation in staged events and television programming. Reports in

the Bangladeshi press suggest that the purpose of such events and

activities is to encourage factory workers to consider themselves part

of the mainstream workforce, even though they still do not share the

same rights (The Daily Star, 2011).

As an annual event, BKMEA arranged the largest knitwear show, the “5th

Bangladesh Knitwear Exposition” on 2-4 October, 2010, at Dhaka Sheraton

Hotel. One of the conspicuous aspects of the three daylong events was

the unique fashion show by the workers. Wearing the attractive outfits

they made, the workers, according to the BKMEA took part in the catwalk

“with pride and pleasure” and it was expected that the unique fashion

show would set a new trend among the workers and the buyers from both

home and abroad to expand the industry.

Furthermore, in 2012, the Bangladesh Garments Manufacturers and

Exporters Association introduced a television “Idol” competition (a

stage reality TV show) named ‘Gorbo 2012’ (literally ‘proud’). It was

screened on Bangla Vision, a private Bangladeshi television channel

intending to find music talent from a particular section (people working

with RMG) of the urban poor of Dhaka, Savar, Gazipur, Narayangonj, and

Chittagong .

The impact of the activities described above can be interpreted in

different ways. I, however, wish to draw attention to the way that in

this context the fashion show and television productions contribute to a

discursive construction of workers that excludes representing hardship

and exploitation. The Gorbo- 2012 story is an interesting case of how

the culture industry operates through multiple agencies and individuals,

even irrespective of their own affiliations, and how it promotes the

hidden governance manuscript of the RGI. It provides an example of the

alliance between media houses and the garments factories, where the

media inevitably snaps up and brands individual innovations. The

objectives of such education is quite clear: to present poor garments

workers in such a manner so that they can no longer be identified as

exotic.

CONCLUSION

The foregoing analysis has explained the modes of labour governance in

the RMG industry in Bangladesh. Formal and informal practices have been

distinguished to demonstrate that even where legislation allows certain

rights to organise and bargain collectively these are difficult to

assert in situation. This analysis bears testimony to workers’

sufferings and violation of various rights including right to form

union. These governance mechanisms also provide financial incentives for

retailers and manufacturers to invest and manufacturers in the EZPs are

exempt from labour laws.

The analysis has also examined relationships between key institutions

responsible for governing the implementation of law and maintaining

order in the factories; that is between the government and its

bureaucratic apparatus (i.e., ministries, agencies, and police force),

manufacturers, global retailers, trade associations and NGOs. It depicts

that how these actors attempts to make RGI competitive without

addressing workers’ sufferings. Theses controlling mechanisms is quite

unique as the use of force and consent creates hegemonic order.

Apparently, the consensus appeared to be an indirect force, to accept

their sufferings and decline of their living standards. These examples

(of workers sufferings) are reflective of the disjuncture between

dominant transcript and actual experiences. Though a number of agencies

discussed are involved in direct control and thereby limit the

articulation of rights, whereas others are engaged in monitoring and

advocacy. Scott’s notion of ‘hidden and public transcripts’ is useful to

locate particular actors in particular social settings, whether they are

dominant or they are oppressed. According to Scott, these methods are

effective in situations where domination and violence is used to

legitimise actions and maintenance of the status quo (Scott, 1985: 137).

Therefore, in the present article we can see a unique governance

mechanisms of force and consent in one side and legitimization of those

mechanism from the other side.

The article also provides an account of the political power relations

underpinning the “worker/employer” constellation in the RMG sector by

investigating the formal and proto-formal arrangements/provisions

underpinning these relations. These arrangements have been derived from

broader institutional provisions which include securing labour rights,

regulatory provisions, code of conducts and progressive narratives and

lead to accounts of the agents involved in promoting these, or

detracting from them by situating all of this in a broader (political)

enabling context.

The buying decisions of global retailers are rarely effected by the

working conditions in garment factories unless supply is disrupted.

Changes in buying decisions, along with shifting their import

destinations, do not change or affect the local manufacturers, but

jeopardise the dependent workers who enter in this employment field with

the notion of development for themselves and for the country. My

analysis of the intersection of the formal and informal modes of

governance that produce working conditions in the RMG industry in

Bangladesh indicates that it is very difficult for workers to organise

and pursue claims for improved conditions and wages. Despite the

rhetoric of economic development, workers are exploited and this exposes

the fault lines of globalization and showing the contingency of hegemony

.

REFERENCES

Ahmed S (2004). Bangladesh: Past and Present; APH Publishing, 2004.

Bradsher K (2004) ‘Bangladesh is surviving to export another day’ The

New York Times, 14 December 2004,

http://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/14/business/worldbusiness/14bangla.html

Brooks EC (2007). Unraveling the Garment Industry: Transnational

organizing and Women’s Work, University of Minnesota Press.

Dannecker P (2002). Between Conformity and Resistance: Women Garment

Workers in Bangladesh, Dhaka: University Press.

Donado A, Wälde K (2012). Globalization, Trade Unions and Labour

Standards in the North, Employment Sector Employment Working Paper No.

119, Published by the ILO, Geneva.

Elliott KA (2003). Labor Standards, Development, and CAFTA in

International Economics Policy Briefs, March 2004; Number PB04-2

published by Institute for International Economics and the Center for

Global Development.

Enloe C (2012). “The Mundane Matters”, in International Political

Ecology, Volume 6, Number 1, 1 March 2012.

GoB (2011). Bangladesh Labour Act, 2006, Ministry of labour, Government

of Bangladesh.

Gramsci A (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio

Gramsci. London: Lawrence &Wishart

Granovetter M (1992). “The Sociological and Economic Approaches to

Labour Market Analysis: A social Structural View”, in Granovetter, M;

Richard Swedberg (eds.): The Sociology of Economic Life, Boulder:

Westview Press, pp. 233-264.

Humphrey J, Schmitz H (2004). “Governance in Global Value Chains.”

InLocal Enterprises in the Global Economy: Issues of Governance and

Upgrading, ed. Hubert Schmitz. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hugill P (2006). The Geostrategy of Global Business: Wal-Mart and its

Historical Forbears. In Stanley R. Brunn, ed., Wal-Mart in the World

Economy Routledge, pp. 3-14.

McMichael P (2010), ‘Changing the Subject of Development’ in P McMichael

(ed). Contesting Development: Critical Struggles for Social Change,

Routledge.

Majumber P, Zohir SC (1996). Garment Workers in Bangladesh. Economic,

Social and Health Condition, Research Monograph 18, Bangladesh Institute

of Development Studies (BIDS).

Nazneen S, Naomi H, Maheen S. (2011). National Discourses on Women’s

Empowerment in Bangladesh: Continuities and Change, IDS Working Paper

368, published by the Institute of Development Studies, UK.

Rahman M, Bhattacharya D, Moazzem KG (2008). Bangladesh Apparel Sector

in Post MFA Era: A study on the Ongoing Restructuring Process, Centre

for Policy Dialogue, Dhaka 2008.

Sachs J (2005). The End of Poverty: How we can make it Happen in our

Lifetime? Penguin Press, 2005.

Saurin J (1996). Globalisation, Poverty, and the Promises of Modernity,

in Millennium – J. Inter. Stud., 1996 25: 657

Siddiqui A (2001). Bangladesh: Human rights in Export Processing Zones.

Asian Labour Update, Issue: 38 on Export Processing Zones (January -

March 2001).

Scott J (1990). Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcript

(London and New Haven). Yale University Press.

Scott J (1985). Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant

Resistance, Yale University Press.

- USAID (2008). The Labour Sector and US Foreign Assistance Goals:

Bangladesh Labour Sector Assessment, USAID, 2008.

|

|